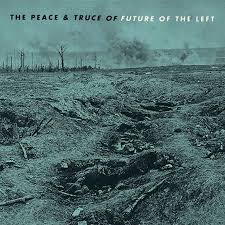

First impressions of ‘The Peace And Truce…’ is that FOTL’s fifth studio record is business as usual for the Welsh rock unit – now a trio once more after guitarist Jimmy Watkins’ recent departure.

Steve Albini’s influence continues to dominate – in particular that of the bespectacled bastard’s ‘minimalist rock’ act Shellac (see ‘The Limits Of Battle Ships’) – as does the tone of camp wrath and general piss-taking, while yet again “The Peace And The Truce…” is another stonking album from a band who in a perfect world would be bigger than Jesus. But listen closely and you’ll detect, beneath the crunch, a new flavour: the genetics of early post-punk, albeit smothered in disgustingly corrosive rage-music.

While much of their previous album ‘How To Stop…’ was all binary broad-strokes – kind of like a noise-rock spin on Pixies’ loud-soft dynamics – here we have a less ideologically sure template, in the true spirit of post-punk and the confused, paradoxical world the genre painted; a less simplistic, more ambiguous sound, closer in construction to the tangled moral mires of post-punk greats The Pop Group, or a more scream-y The Raincoats, or even post-punk’s mavericks This Heat but with added heavy low-end (see ‘In A Former Life’), better able to articulate Falko’s complicated outlook on life.

The lead man, whose sense of bitter British-made irony and absurdist comedy (belying, of course, the fury of a moralist) is pure post-punk, now has a more sophisticated and expressive musical backdrop to work with, in which he can better explore this complex culture of ours via his favourite subject matters…namely hypocrisy, the sins of the British alpha male and modern life’s increasing pointlessness – and on ‘Back When I Was Brilliant’, where best to eat Thai food when in Hamburg.

Essentially it’s post-punk with a comedian for a spokesman, only with every idea delivered in the form of a hard, unpretentious gut-punch and with the utmost degree of irreverence. The rhythmic funk, the prominence of the bass guitar in the newly spare arrangements of a three piece act – all very post-punk. ‘No Son Will Ease Your Solitude’ could be a hard-rock Magazine, while ‘50 Days Before The Hun’, whose combination of horror synths and raspberry-blowing kazoo tells you all you need to know about FOTL’s jaundiced view of society, takes its cues from post-punk progenitors Bauhaus and the goths’ proto post-punk howl.

More macabre still, on ‘Reference Point Zero’ Falko’s demonic refrain of “Shake Rattle and Rolllllllll” gets right to the heart of darkness in the lead man’s cynical soul.

“The Peace and Truce…” doesn’t boast ‘How To Stop…’s wealth of tunes – sometimes a necessary sacrifice when forging a sound as opposed to songs – but by the same token, little of the material is what you’d call ‘art-music’. ‘Grass Parade’ and the aptly named ‘Running All Over the Wicket’ are sped-up punk barnstormers conceived with only one purpose in mind – pleasing live audiences, while the album’s best track, ‘Back When I Was Brilliant’, resembles an austere, deathly take on Zeppelin’s mega-blues. Hard as fuck, smart as fuck, as much brains as brawn, is there a more essential British guitar band around than Future Of The Left?

Filed under: Uncategorized

This February I finally made it Jamaica. For some music fans, to visit Jamaica is like pilgrimage to Mecca.

This little island changed everything, to the point where it’s frightening to think what the last forty years of London culture would look like had the 60s emigration never happened. More so than any other world city that received the diaspora, West Indian culture changed London.

You can imagine an alternate reality where we’re still listening to Status Quo albums and hammering peak-era eurotrance. There’d be no jungle, dubstep, grime or garage, while post-punk would have been half the future-shocking art-form it was. Even British house music in the present day would be unrecognisable. And even though we could really have done without UB40, and even though my holiday was less Trenchtown and more Thompsons all-inclusive, to be sat on the beach in Montego Bay surrounded by the ever-resonating juju that made modern-day Britain was nothing short of dreamy.

On the second day we hit it off with one of the bar men, Shane, a big grime fan as a result of his cousins in Hackney who had turned him on to Lethal and Dizzy. I asked him about the local music scene, and the first thing he tells me to look out is Alkaline and the “biggest track of the year” – ‘Champion Boy’.

Alkaline, stage name of 21-year-old Kingston MC Earlan Bartley, has been on the radar for a couple of years now (check out the ‘Noisey: Jamaica’ feature from last year), but the runaway success of ‘Champion Boy’ has left Bartley on the cusp of becoming Jamaican dancehall’s next global export. Using the very fierce ‘Fire Starta Riddum’ written by Jamaican riddim queen, DJ Sunshine, whose ‘Wul Dem’ riddum swept through dancehall in 2014, ‘Champion Boy’ is all over the island, blasting from out of crowded city streets, from car stereos, from Jamaica’s homespun music channels and adverts for Premiership football matches, energy drinks and used cars. It’s nothing less than a phenomenon.

February is black history month in Jamaica, as well as both official ‘reggae month’ and anniversary, on the 6th, of Bob Marley’s birthday. So it was a great time to be in Jamaica if you wanted to get a sense of island culture. In addition, the third week of February is the unofficial start to the holiday season, just in time for incoming tourists to meet headlong with the ‘Champion Boy’ craze, and perhaps spread the word internationally.

But this February also sees Jamaica’s national elections, to be held on the 25th. Everywhere we drove were crowds of supporters klaxon-beating on the roadside or dancing and singing at rallies. On reggae island, of course, politics and music are almost interchangeable, and even politicians are jumping on the Alkaline bandwagon. For example, former prime minister and leader of the Jamaican Labour Party, Andrew Holness, takes to the stage at rallies to the strains of ‘Champion Boy’s chorus. It’s of course not the first time Jamaican politicians have co-opted the local charts. In the mid 70s, the JLP and the opposing PNP (People’s National Party) fought for the public endorsement of Jamaica’s first global superstar, Marley. After agreeing to headline the ‘Smile Jamaica’ concert – organised by JLP leader and then prime minister Michael Manley – Marley, his wife and manager were injured in an assassination attempt at Marley’s home.

Alkaline is part of a new generation of ‘post-Vybz’ MCs, who came of age subsequent to Jamaica’s infamous late-noughties ‘reggae wars’ – accompanied by a drastic increase in levels of gang violence across the island as locals chose sides. Staged between Vybz Kartel’s ‘Gaza’ crew from the Jamaican town of Portmore and Kingston’s ‘Gully’ crew – led by dancehall star Mavado – the feud came to an end in 2011 with the arrest and eventual sentencing of Kartel, for the murder of Clive ‘Lizard’ Williams. Kartel’s sentencing in 2014, meanwhile, came shortly after an American-backed operation to arrest and extradite drug lord (and ‘Gaza’-benefactor) Christopher ‘Dudus’ Coke in 2013 went awry, resulting in the massacre of 73 civilians in Kingston’s notorious ‘garrison-hood’ Tivoli Gardens, effectively breaking the back of the city’s organised crime culture.

You wonder what Jamaica’s reggae forefathers have to say about the likes of Alkaline. With the MC’s famed ‘demon’ lenses and (allegedly) ‘whitened’ face, his iced auto-tune settings and snarled, triumphalist delivery – speaking of the very coldest states of advanced materialism – ‘Champion Boy’ feels about as far as dancehall has ever travelled from roots reggae’s Christian beginnings. Glamorous toy-town gangsters like Alkaline lined the walls of every club I visited, dripping in bling, walking the room like a train of reflective surfaces and sexual intent. On the other side of the club were their preening female counterparts, cold and imperious and dressed like sci-fi royalty. It’s owing to Jamaican revellers like these that some locals I spoke with predict a coming backlash against club culture and a resurgence in the popularity of street-level sound system parties, where posing and conspicuous consumption isn’t tolerated. In one of Montego Bay’s big local haunts, Margaritaville, I spoke to one teenager, Avion, who wasn’t so keen on the this new strain of dancehall: “I am a Christian. I like Toshe, Congos, Ken Boothe…but I can’t hear no heart to this music.

But while Jamaican dancehall is currently in peacetime, the actions of one unlikely provocateur perhaps threatens to de-stabilize the scene, in this incidence fuelling tensions between diehard Gaza disciples and Alkaline’s own Kingston crew, the Vendetta clan.

Back in 2010, returning Olympic hero Usain Bolt took to the DJ Booth during his victory party and declared that only ‘Gaza’ tunes were to be spun. “And anybody nuh like dat” Bolt added, according to The Village Voice “can jump inna gully”. In October of last year, during Kingston’s premier track showcase night ‘Uptown Mondays’, the Gold medallist again took to the stage, to diss Alkaline directly. “One likkle youth a try imitate the Gaza youth, mi nah call nuh name … three blind mice, three blind mice [a reference to Alkaline’s lenses]” Bolt hollered, “All when him incarcerate and a easy himself. When the boss come a road, hear mi a seh? I will be downtown for the Gaza Boss, hear mi seh,”

Bolt’s comments caused a furore in Kingston. In response, a month later Alkaline released ‘Champion Boy’, taking not-so-subtle aim at Bolt and by extension Vybz, who Alkaline and co. perhaps feel cannot sustain his dominance from behind prison walls for much longer:

“Champion mi a di Champion Boy

One bagga gold medal pan mi eno

Champion Boy yuh kno di damn thing guh

Pan a podium a sing di anthem tuh

Dem yah story yah cyaa guh pan ER

it affi guh pan profile”

According to Jamaica TakeOut, Alkaline has teamed up with ‘Gully’ kingpin Mavado to record a medley of their ‘Fire Starta’ tracks.

Sources close to the recently MC had this to say: Alkaline been working overtime in studios, recording several tracks per day and lowkey shooting multiple music videos. The plan is to outrank Worl Boss [Kartel] during the year 2016.”

Though seminal-feeling for its sheer anthem-ness, if you factor in as well the single’s success you can easily imagine ‘Champion Boy’ coming to represent a changing of the guard moment for Jamaican dancehall – the new wave declaring that the King is dead, long live the Champion Boy.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Much like all massive cockheads, the only thing i’ve ever really wanted out of life was to be cool. Never quite got there, though. Nope. And given that unless your Gianni Agnelli, Bill Murray or in Swans, no man aged 34 year or older can ever truly be cool, it’s clear that ship has sailed.

I tried cool dancing, but the end product was too camp for the purposes of heterosexual union (two bars into The Sunshine Band’s “I’m Your Boogie Man” and my ass grows a mind of its own), or doing cool things like a ski season in France when I was 22, until I developed a lower back skin infection my unnervingly glib Alpine doctor explained was essentially medieval in nature. I flirted with hip hop culture but was too quarter-Jewish (my mum’s side), and being a rave-geezer, but ecstasy gave me depression, and Manc monkey, but bucket hats made my massive head looked positively Merrick-like.

Yes I even tried fashion, until it quickly became apparent I’d inherited my Dad’s sense of style, a dyed-in-the-wool Ulster Presbyterian who for some reason when in jeans simply cannot look like anything other than a Weeble in dungarees. We can never get it quite right, me and my dad. The man has a red Christmas shirt like the Piper Alpha disaster while for a short period in the early Noughts in an effort to get in on the 80s revival thing I took to sporting a white headband. I looked like a slightly rotund man sporting a white headband. All told, when it comes to fashion I’m Don Cheadle’s character in “Boogie Nights”, sitting alone at a party dejected, garbed in Rik James soul-beads. Even as I write this, my new white jeans are riding a bit at the crotch. It’s my belief that all so-called “creative” types are basically psycho chameleons shuttling from skin to skin without a true self to call their own and when during one of my many dark nights of the soul I ask the darkness “Who am I, darkness. Who is John Calvert?” one thing that always comes to mind is, believe it or not, Hannibal Lector’s description of serial mischief maker Wild Bill: “Billy is not a real trans-sexual, but he thinks he is. He tries to be. He’s tried to be a lot of things, I expect.”

So I’m not cool. I’m just not, especially on paper. There’s the eczema, a pretty bad nut allergy and the permanently wheezy chest (my flatmate recently claimed she can hear me breathing from the next room), a bottom shape that some have described as womanly and features too bulbous to be considered classically handsome (imagine Bobcat Goldthwaite with a low white blood cell count). Too teary for aloofness, too itchy for wit, too silly for insouciance, my track record with the opposite sex reads like a history of mental illness in Soviet Hungary. I once dribbled on a first date. Not like a teardrop type dribble – a massive stringy phlegm which, after hanging momentarily from my chin, landed on the table with an audible drip like a bad joke. There I sat, an idiot Rudi Völler with a dreggy pint and fuck all to live for.

On occasion, however, against my better judgement, I have felt cool. Like when I was in a punk band for a bit, or when I got better at smoking inn 1997. Invariably though, down the years I have felt at my most cool when confusing hipness with watching hip films or listening to hip music. As an 11 year old in 1991 I had been cognisant of the fact that hip hop and hardcore were in fashion. But to the 11-year-old me, grunge, alt rock and the pains of Generation X – for all intents and purposes American counterculture’s last hurrah – was cool; the slouching, the fatalism, the soul-vomiting, the self loathing…mind blowing to a child of the 80s where cool had meant Tom Cruise in a letter jacket, wet look Rob Lowe, yuppie self-actualisation, 50s nostalgia. To this day it’s still my opinion that iconoclasm is never as righteous as when delivered in the form of complete and utter give-a-fuckness. That Cobain could be famous and cool and talented yet not give a fuck about any of it was staggering to me, and when the blonde one did finally check out in April 1994 to me it wasn’t a tragedy so much as the ultimate act of non-conformity, the ultimate shrug, a bored sigh, in the face of Reaganite self-improvement. As a statement it was the opposite of self-improvement: total and final self-destruction.

I so wanted to be sensitive 90s man, or one of Gus Van Sant’s beautiful boys: the pretty freaks lost in the American heartland in some dream of themselves, or Billy Corgan in the ‘Today’ video, Kiedis singing about heroin on the streets of L.A, Kurt Cobain, whatever, never mind. So sad, so weird, so deep, to my teenage self. Somewhat problematically, however, I was never really a very sad teenager, or particularly weird. My parents weren’t divorced, I had no drug problem to speak of and I was never bullied, unless you count the time my mates and I had a falling out and I spend a whole summer with a 1st year from next door called Brian McFerran. He taught me ping pong that summer, and oh how we laughed. And the only time I ever remember being sad was when my older brothers had a fight on the kitchen floor and my mum wept screaming “You’re a beast you’re a beast!” at my eldest brother and swatted them with a rolled up Women’s Weekly as if they were a couple of horny dogs.

Nonetheless it never stopped me trying to act sad, which I did by wearing a black heavy hooded raincoat around the house until my mum explained to me that it had once belonged to my Jewish Grandma, or pushing my too-frizzy curtains away from my face like a slo-mo River Phoenix. In the end though I was shit at depression in the 90s, but I really thought it was so glamorous to be fucked up. Of course, the real thing would arrive in good time, which was a bout as glamorous as chasing a pig.

But I never felt cool the way I did when, aged 16, the holy trinity of Danny Boyle, producer Kevin McDonald and screen writer John Hodge introduced me and probably a large chunk of the British teen populace to the idea of British cool: squalid, self-destructing, self-serving, filthy, cold, severe, cruel, pitiful and vulgar British cool.

Where I grew up, in Northern Ireland, British (or “mainland”) popular culture is in fact broadly speaking something the Northern Irish don’t relate to very easily. Rather our affinity has traditionally been with American culture. We like are dancing in lines, our politics Christian Right, our rock Southern-fried, our alt-rock sylvan Seattle-bred and our pop stars strictly Elvis and/or Bruce-shaped. Gentlemen soldiers, withering cads, irony, English dandyism, sartorial sophistication, literary erudition, afternoon tea, kinky aristocrats, androgynous synth pop boys, art-school posers, bands named after Italian Futurist manifestos, Suede: theses thing don’t fly in Puritan Ulster; too posh, too mince-y, too conceited for a country where tallest poppy syndrome is epidemic and where being a funny person and one of the gang is the only yardstick that matters, and too precious and too decadent for a nation of shipbuilders and farm boys where the acoustic guitar is king, where there is only family, work and death, and where art is humble, hard, heavy, honest, substantive, worthy, blue, real, raw and always literal. Flyover America in six counties or less.

But Trainspotting changed everything, for me anyway. Almost immediately anything American, including American underground music, was about as cool as Noel Edmunds in hell. Which incidentally is probably where the bastard belongs. Firstly, by 1996 the American underground wasn’t what is used to be. The slacker culture part of the movement began life as both an exciting new voice in American counterculture and an authentic freak scene (see the life as lived by the cast of proto-Harmony Korine weirdos in Linklater’s quite bizarre eponymous debut), but by the around 1993, which was just around the same time as post-grunge first reared its ugly head (second only to acid jazz as the least cool and most irritating sub genre of all time; Matchbox 20 rot in hell) and the Fade To Black-inspired, nihilistic Melvins-through-Mudhoney punk element disappeared from grunge, slacker-ism had in actual fact begun to smack a little too much of 60s revivalism.

There’s a reason why it’s Iggy, Reed and the doomed, dangerous flip side to the hippy dream and not Simon & Garfunkel that features on “Trainspotting” (aside from the heroin connection of course). Because, the 60s and the hippy movement were a lot of things, but cool they were not. All those notions of egalitarianism, humility, mutual respect, aspiration, nature worship, happiness and altruism were too noble to be cool. Vanity, anxiety, greed, desire, boredom, violence, meaninglessness…this is the stuff of cool. As Burroughs once wrote on brainyquotes.com: “Would you rather be a snake or a poisoned snake?”

Being weird and fucked up like Cobain was cool, but after Trainspotting, being a bad person was cooler; especially when unapologetically, when the final outcome is your own complete self-annihilation, and when framed in Trainspotting’s sense of the absurd and the film’s cunty pitch-black humour that could only be British: too petty and self-defeating to be Scandi in origin, too nervous and bleak to be Southern European, too, well, funny to be French, and basically not fucking bonkers enough to be Balkan.

Suddenly Cobain was a mumbling Emo complainer compared to the puckish laughing boys crashing out of Trainspotting extremely savvy, pretty fucking cool marketing campaign. It was love at first sight. There must be a clean score of Kodaks from the late 90s in which I’m giving it the full on Macgregor two-fingers-to-the-camera thing, regardless of the occasion. Quite embarrassing, really, though decidedly not as embarrassing as my “Fight Club” stage when I wore a Hawaiian polo shirt two sizes short for me like a palm tree-printed Honey Boo Boo and got beaten up by my flatmate.

Far cooler, you see, was the music of post-ideological, post-morality hedonism: British electronica and dance music, which Boyle was the first director in cinema to have the good sense to harvest, for massive cinematic returns. Anything new is automatically cooler than what came before it, especially when you consider that alt rock had by 1996 resorted to reactionary Baby Boomer nostalgia (stand up, Evan Dando).

But British dance music was fucking cool: stylishly sheer, thrillingly cold, impossibly vital, illicitly crepuscular, chicly avant but brutally hooligan with it, and most importantly modernist, both in its technological nature and its amorality, More than that, it was NOW, back when ‘now’ in music meant exactly that. Moreover, there’s nothing teens love to do more that call bullshit on bullshit. It’s the essence of hipness. And saving the world, Cobain-style, was now bullshit, of the cheesy American variety.

Dance music was truer to the realities of life (like, REAL, man), more honest in its unashamed dedication to the pursuit of pleasure and in its anonymity, which prohibited the creation of false idols and grand myths. It was also a drug culture, and as every teenager knows, drugs are cool.

Above all else, the establishment hated it. For the 90s teen, what was not to love? For all the self-loathing on show there was always a decidedly rockist idea underpinning American alt-rock that Cobain were the good guys and their enemies in the mainstream the baddies, making the world a better place; the implication being that ‘they’ on the margins were better than the squares, with their M Bolton records and G’n’R T-shirts. All told, it was too much like heroism, or triumphalism masquerading as humility, and essentially narcissistic. In Britain though, and in the great tradition of British miserabalist art, there are no goodies and baddies, only cunts. Cunts having a fucking great time. Or as Renton puts it, our boy peering out onto a strobing dancefloor scene of futuristic revelry sound tracked by Bedrock’s “From What You Dream Off” in one of Trainspotting’s most iconic lines: “The world is changing, music is changing, drugs are changing, even men and women are changing. One thousand years from, now there’ll be no guys and no girls, just wankers.” As Richard Corliss said of the film at the time is his review for Time Out, “[Trainspotting] is a film about joy, in conniving and surviving it.” By the 90s, joy was the new and self-serving religion of Britain’s first post-political, post-modern generation: the chemical generation.

Underworld’s “Dark And Long” fires the cold turkey sequence. A very British kind of dance track, or certainly European, it’s the type of feel-bad, highly-strung, frigid aesthetic that American house producers see as futile and self-defeating but which contains the right measure of amphetamine thrust us pasty Brits need in our dance music in order to expel our dense frustrations through the medium of slightly angry body movement. Suffice to say, voyaging and hallucinatory the track also provides a perfect backdrop for Renton’s fractured terror-ride through junky limbo.

Sleeper’s cover of Blondie’s “Atomic”, sound tracking Trainspotting’s brilliant shagging sequence, though neither British in origin nor technically a dance song seems in the context of the film somehow cut from the same cloth. There’s something very ‘dance music’ about “Atomic”s flat new wave structures, it’s square 4/4 rhythms, its stiff white funk and its overt synthetic-ness – a sound formulated in what is essentially America’s European satellite state and homaging the Europhile wonder-producers of disco – and something decidedly British about the song’s weary doom, its refinement, its tacky glitz, Harry’s suburban Saturday girl dreams (“Tonight, make me magnificent”) and the way the singer’s dispassionate vocals undercut her band’s gleaming pop, to speak of so much joyless decadence and pleasure-fatigue. It’s basically the dirty, nervous neon oblivion of last orders provincial Britain made sonic, and so therefore played beautifully with the scene; a scene which in turn came to enjoy a symmetry with Pulp’s epochal “Common People” released the year before Trainspotting, and its most brilliant of lyrics: “And then dance and drink and screw / because there’s nothing else to do.”

But of course it’s Underworld’s other contribution that will be always be best remembered. Reportedly named after a greyhound the Barking duo once bet on, “Born Slippy” traced a lineage between the punk experience and rave’s lumpen heart; the eight minute apotheosis of what began in baggy, its lairy but beatific, rabid but rapturous wave of unstoppable freeform evoking spidery casuals raging through Balearic beauty, shouting LAGER, LAGER LAGER.

And no one it coming. Who could have predicted that a relatively formless, overlong B-side studio-jam could go on to bottle both lightning and the Brit zeitgeist in one fell swoop, while sneakily subverting the same 90s lad culture it aggrandised. If Britpop alienated you, with “Born Slippy” you felt proud to be British. It was a national anthem in the dictionary definition of the word: a rousing patriotic song adopted by a country in expression of national identity. The dance anthem was born.

We were too late for rock and roll, rave, glam, disco, synthpop, and the best part of grunge, but those who would dub us 90s teens as generation too-late were never sixteen the summer “Born Slippy” came out; the type of song that brings your whole life into sharp focus.

Every time I hear those iconic opening notes it’s 1996 all over again. I’m sat in my backyard in the glorious late afternoon sunshine of that hot June, pretending to revise. Just a perfect day. England Euro ’96 is turning London into the biggest, happiest party in the world, Oasis are about to play Knebworth and finally I’m leaving boyhood behind me, indicated by the sudden meteoric growth in the size of my neb. I feel like a man. A very cool, albeit very little, man, because that’s how listening to the exotic, mysterious sounds of adulthood can make a teen feel. And I’m watching as my big sister’s mates, tanning themselves beside the birdbath, their school shirts rolled up to expose vanilla forearms, flirt outrageously with my older brother, who at this point is beautiful, crowned with a shock of black-brown hair, and who incidentally had four months prior at the exact moment the needle perforates the smooth skin of Renton’s forearm passed out in a cinema in Dundee.

As for the electronica, we were offered up two absolute gems. Primal Scream, taking a break from peddling massively overrated “dance rock fusion” and/or ripping off The Stones, lent the film the eponymous “Trainspotting”, from what in my opinion is really Bobby and co’s only good album – “Vanishing Point’. Playing over the park scene, where Renton and Sick-Boy talk shit and shoot a dog with a high powered air rifle for their mild amusement, with its trip-hop rhythms, woozily surreal FX and the sense of inertia conjured by its Morricone-esque percussion and flat, droning trajectory the track captures perfectly the daytime ennui particular to British summertime, when the lingering fug of dark activities dulls the sunlight. I’ve always thought the photography is fascinating in that scene, those summer colours muted to the oranges and greys of sick psychology by some invisible filter.

“One Last Hit” meanwhile, from Leftfield, which was released as a split single with “Trainspotting” is just pure inner city Britain: subterranean, dank, oppressive, dread filled dubtronica shot through with bad intentions. Written for the film, the track chimes beautifully with the sense of impending doom Boyle’s clipped, heightened direction creates (see, for example, the ever so slightly sped up establishing shot of the coffin like coach), as the friends make their way to London down a Stygian motorway and Renton presses the self-destruct button once again. “There’s final hits and final hits. What kind was this to be?”

But arguably the film’s coolest moment arrives comes in an unlikely form in the soundtrack’s very least cool dance track: eurodance rapper Ice MC’s ‘Think About The Way’ deployed to ironic effect over the tonally jarring tourist vid of booming 90s London, all bright eyed euro teens, scampish Pearlies and 90s optimism as Renton arrives in the capital to get him some of that neo-Thatcherite action. Forget the Iggy tunes, this is Trainspotting at its most punk, in the most mean-spirited sense of the word, with Boyle sneering at the happy idiots and their ignorance to the truth: that the 90s was just the 80s with better PR. Fucking each other over to get ahead is as British as red busses and queues. So why indeed would you ever ‘choose life’, the rat race, when it is no more or less worthy a life to be a junky?

Trainspotting was a morally ambivalent film; full to the brim with smart arse cynicism every bit as chic, acidic, sickly and angular as its smart-arse protagonist. The Britpop movement some say was a bit cunty; espousing of a reactionary, fundamentally middle class, all too white concept of painfully retro Britishness right at a time when rave, 80s synth, trip hop and a nascent jungle scene where moving Britain and British music into the future, while at the same time uniting class, sexuality and race (See the Libertines and their Albion, ten years later; indie’s inevitable backlash to UKG perhaps?).

Professional crybaby but good writer, and leader of eminently average Britpop also-rans The Auteurs, Luke Haines famously described Britpop as something like a bunch of art school pricks feigning working class laddishness because they felt emasculated by Thatcher. In my opinion, however, the Britpop bands were right to hit back at the so-called American cultural imperialism of grunge. Even if their version of Britishness was bogus, British it remained – restoring a much-needed sense of campness, sex, wit, irony, glamour and humour to guitar music. And neither do I begrudge Boyle for including the Britpop bands in his film. The director rightly recognised that, for better or worse, these bands defined the era, and so were an essential inclusion for any film about Britain in the mid-90s.

However, Boyle does overplay his co-option of trendy Britpop on a few occasions, most notably in the inclusion of Elastica (“2.11”) led by the deeply unpleasant Justine Frischman, who represented all the worst aspects of Britpop. A self-regarding dour pseud who thought that making self-regarding dour post-punk put her on a par with her hip, eminently less self-serious post-punk heroes while elevating her above Supergrass because her 2-d retro-ism was built from the work of more obscure bands, Justine was the poster girl for the drearily mediocre London art-rock side of Britpop. These days, whenever it feels to me like the capital’s music scene is full of wankers, I remind myself that the Britpop era must have far worse with narcissist frauds like Frishmann in power.

“This looks easy” narrates Renton “But it isn’t”. For all its edgy nihilism, Trainspotting was a sad film. One thing Welsh understood implicitly is that while dropping-out is rebellion, the marginal life is also one of melancholy; the melancholy of alienation, purposelessness, of dislocation, and oblivion – the oblivion into which Renton dives headfirst from the wall behind the pub (my very favourite sequence in the film and Boyle’s finest ever slice of visual poetry; lacking in the directors work of late), to the stylings of Blur’s sighing ‘Sing’ and eventually “Trainspotting”s saddest sonic cue, ‘Perfect Day”, as Renton is swallowed whole by his poison, only to be returned to his childhood bedroom in the arms of his father. The end of the tracks. Did Boyle’s film glamorise heroin? Of course it did. This was a cool film set to cool music, populated by dangerous punks and chic wastoids. Even the cold Turkey scene, what should be a sombre cautionary moment in the film, was played out to the stylings of killer techno. Only, in Trainspotting the real tragedy of junkiedom isn’t death, but the misery of the living ghost, who is neither dead nor truly alive.

The book’s title, Welsh drawing a parallel between the existential stagnancy of the junkie and that of the forever waiting metrophile, also derives from a chapter towards the end of the novel. In the chapter, Renton and Begbie are approached by a frail wino while pissing up against Leith Central station, who asks the pair if they are trainspotting and is duly set upon by Begbie. In a truly poignant bit of writing, the man, it transpires, is Begbie’s father. It’s a rare moment of pathos in Welsh’s otherwise stony oeuvre. Boyle picked up on this vein of melancholy running through Welsh’s novel and ran with it. Gus Van Sant’s comparable “Drugstore Cowboy” is imbued with this same sense of anomic deflation, as is the film adaptation of Luke Davies’ heroin memoir’ “Candy: A Novel of Love and Addiction”, another great entry in the drug-movie canon which, like Boyle’s film, conveys the surreal, amnesiac nature of junkiedom when you’re out of time with the world, with reality, and no longer care either way. Camus’ line from “The Stranger” – “Today mother died. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know” – could easily be the words of Renton were it delivered in a strong Scottish accent. Note the similarities in Renton’s “I think Allison had been screaming all day, but it hadn’t really registered before. She might have been screaming for a week for all I knew.” Like the trainspotter, recalled Davies, the junkie orders his life in units of longueur: “They say that for every ten years you’ve been a junkie, you’ll have spent seven of them waiting.”

In many ways, nowhere in British popular art is melancholy more keenly felt than in the good old British pop song. For a pop golden era, Britpop was unusually flush with melancholy, whether it was Pulp channelling the faded glamour of post-industrial Sheffield or Blur and their fusion of Kinks-ian blues and sour post-punk tracks about English banality. Both bands were selected for Trainspotting’s soundtrack, but not just for the fact that a soundtrack featuring hip acts would shift units. Contrary to contemporary critical consensus, these were important bands, essential in documenting and defining what it was to be young and British in the afterlife of Thatcherism, and whose rich and textured literariness and knack for social commentary is unimaginable in white British pop today in this our blank Coldplay-wracked lyrical wasteland. Pulp’s “Mile End” with Cocker detailing his squalid working class existence in pre-gentrified East London, is as good an example of the pop song as tragicomedy as any produced in the post-punk era and therefore serves as the perfect soundtrack to the Trainspotting’s most wretchedly hilarious chapter when a fugitive Begbie and a bored Sickboy gate-crash Renton’s new London dream. Is there anything more British than having a bunch of cunts for mates? When, following the drug deal, the friend’s short-lived bonhomie ends inevitably in a terrible act of violence, the tragic side-on shot of Begbie and Renton, bathed in the jaundiced afternoon half-light of a grotty boozer, captures them in their shared and lowly fate, a condemned Renton staring his future, his enslaver, in the face, as slowly Begbie exhales. The shot sags with a heart-breaking resignation.

There was Eno’s synth inversion of cowboy ennui, “Deep Blue Day”, and Heaven 17’s “Temptation”, a glittering 80s melodrama with oodles of Saturday night desperation beneath its shrill grandeur. Like the dying vestiges of more innocent times, or a fading memory of Rent’s childhood, New Order’s sad-pop classic “Temptation” floats around the periphery of the film – an echo of the 80s which indeed is a decade whose shadow looms large over Trainspotting – with Sumner’s girlish, smitten lyrics cooed nursery rhyme-like by Diane in the shower during the ever mysterious ‘girl on a bicycle’ shot and again in the cold turkey sequence. “Ooh you’ve got green eyes / ooh you’ve got blue eyes…”

But it is Pulp’s “Sing” – in my opinion Alburn and co.’s masterpiece – that cuts closest to the film’s sad soul. Baby Dawn has died, Renton cooks a shot for her grieving mother, but not before he gets his; that goes without saying. If there’s any one moment in Trainspotting that conveys heroin’s toll on the soul, on the user’s humanity, it’s this one. And so on and on they go “piling misery on misery” stealing, running, cooking, falling, as alongside the looping piano line and Alburn’s sweetly sorrowful falsetto – the numbest, faintest expression of hope in 90s guitar music – the vicious cycle of addiction turns over once more, returning the film to its opening scene. “Sing”, like “Perfect Day”, is all about the impossibility of redemption when you’re a honest-to-goodness, card-carrying heroin addict. Happiness is for the normal. Even the film’s upbeat ending – an era-defining film closing with an era-defining track, seems infused with the suggestion of imminent catastrophe. Looking ahead, the day you die.

Filed under: Album Reviews, Album Reviews: Noted Artists, Recommended Albums, The Quietus

If the magisterial TV On The Radio had, by September 2006, acquired a reputation as doomsayers, it was only their response – as true artists – to a geyser of fear in full profusion midway through Bush’s second term – there or thereabouts the very belly of the beast. Two years on and within a tortuous hair’s length of salvation, Tunde Adebimpe hollered on ‘DLZ’: “This is beginning to feel like the long-winded blues of the never”. Now, years after the war, they put the pieces back together again under the soft light breaking over peacetime, LA County.

Nine Types of Light is an album about finding yourself again in the quiet. “In isolation: a transformation” sings Adebimpe on ‘Killer Crane’. In a recent interview with The Guardian Adebimpe spoke about the strain of adjusting his mindset to the new era, after a decade of dread and defence: “Panic can become a very fruitless security blanket and it makes it easy to default to the negative” he confided “…The truth is you’re lucky to feel anything”. On ‘Second Song’ it is the enveloping power of music that stymies Adebimpe’s night-terrors (“when the night comes I’m feeling like a pyro”) and for once he “doesn’t have a single word to say”. Blissed out, with his “restless mind” quietened, he informs us that while we struggle to define the “heartless times’ he’ll be getting down to the business of making babies, like any veteran worth his salt.

On the album’s centrepiece ‘Killer Crane’ Adebimpe departs their new lodgings in Sitek’s LA digs and travels out to the Pacific; the trembling low-end building the suspense. On the edge of America he releases his trauma, memories and dark thoughts to the wind, in the form of the titular representation / psychic projection / power animal / wot-not. The killer crane soars “after the reign / after the rain-bow”. Over the chorus’ flower-child woodwind and cello-like synths he remembers the times before the strife, a vision of long-ago happiness he once dreamed about on the frontline: “Sunshine / I saw you through the hanging vine / a memory of what was mine / fading away”. It ends in mellow harmony, with a couple of strums of acoustic guitar flicking the switch off again. Adebimpe is “suddenly unafraid”. Truly a timeless depiction of redemption.

To paraphrase Ron Kovic, it’s as if for TV On The Radio America feels like home again. Bathed in a dusky vapour, the euphonious opening three tracks exhale nine years of tension. The first – ‘Second Song’ is a study in relaxed simplicity. There’s church organ, a piano and a crescendo that positively gleams. Whereas before the horns and brass would convulse and alarm, on Nine Types they pump your chest full of melodic goodwill, while the synths at the beginning of ‘Keep Your Heart’ – gossamer, pinkish chem-trails – might have been molten and diabolical a couple of years back. Then there’s the woozy little fireflies spinning and flitting around the verses of ‘You’ or the plaintive oriental xylophone at the start of ‘Will Do’. “The plan was to make music in real life, for real life” Sitek told Rolling Stone. Throughout, the arrangements are sketched and the production is unobtrusive and forgiving, shorn of the hi-tech grandstanding of yore and culled of both that beastly quality and the live-wire paranoia that plagued the high end, while the vocals are one-take and unfinished. As opposed to the poly-rhythms of before, its most transcendent moments are steadied by Bunton’s metrical, softly luxuriant hip-hop beats. Exampled in the barely perceptible (but indispensable) electric caramel that coats the YYY’s ‘Turn Over’ and ‘Gold Lion’ it’s Sitek’s skill as a handsome texturologist which benefits Nine Types… most keenly.

It’s not all tenderness and summer evenings though. As Adebimpe attests on the twitchy ‘No Future Shock’ he still sleeps with his gun. The ogreish funk carnage kicked upon ‘Repetition’ echoes the thoughts of men constantly looking over their shoulders, eyes peeled for the next sign of danger “the cracks will be obvious before too long” Adebimpe frets on ‘Repetition’. A throwback to Return To Cookie Mountain, the swaying and brilliant ‘Forgotten’ is a typical New Yorkers’ take on the Orange State, full of mordant foreboding and talk of plastic paradise. It’s a strange land they’d rather just forget: “Hold tight / our lover’s day written into the sky / we’ll fade into the night” caterwauls Malone. Final track ‘Caffeinated Conscious’ almost sounds like Faith No More while ‘New Cannonball Blues’ is stern and domineering (unfortunately save some swooping Stevie Wonder-like brass, like ‘No Future Shock’ its a very stilted, uninspired relation to the vibrant pop-funk which populated Dear Science).

Since their inception the Brookynites have obsessed over a cataclysmic idea of romance, forever married to the defiant image of those lovers kissing beneath the shadow of the Berlin Wall – “and the guns, shot above our heads / and we kissed / as though nothing could fall”(they even went as far as covering ‘Heroes’ for the War Child album). It’s a macabre notion of romantic endeavour best summarized on Dear Science’s ‘Stork And Owl’ as such: “Death’s a door that love walks through / in and out / in and out / back and forth / back and forth”. The dilemma is, how do they sustain the passion of love in their love songs, when their protagonists are no longer shagging like it’s their last night on earth? The quintet have always appeared to subscribe to Oscar Wilde’s view that the only true romance is a doomed one. “They spoil every romance by trying to make it last forever” quipped the writer, “…the very essence of romance is uncertainty”. Now that life seems less perilous, is the power of their heartbreakers somehow depleted? Another of Wilde’s truisms comes to mind – his conviction that “Where there is no extravagance there is no love”.

Nine Types of Light offers a far less opulent, dramatic ecology when compared to their earlier work. But it speaks of a more mature, less fatalistic, more realistic notion of love; one of caring, understanding, patience, soulful connection. Obviously it’s a less arresting interpretation, but it grows on you until its lambent warmth is in your bones, much like the album. The bombs no longer fall but “we’ll fall together in time, just the same…” Adebimpe harks on ‘Killer Crane’. More poignantly in the context of the entire album and TVoTR’s new musical era, as he sums it up on ‘Will Do’: “You don’t want to waste your life in the middle of a lovesick lullaby”. John Calvert

Filed under: Album Reviews, Album Reviews: Noted Artists, Recommended Albums, The Quietus

After a run of relatively oblique collaborations, Interplay sees John Foxx’ return to the role of pop architect, ably assisted by The Maths (aka Ben Edwards, Benge) who has graduated here with flying colours from studied technologist to certified song producer. With his memory banks reset by Edwards’ box of retro delights, Foxx has taken the opportunity to reassert the grand arches of the mind on the pop of his salad days – a formula which rapidly became intellectually superficial and increasingly less expressive in his wake. Foxx’s methodology seems to be “Elaborating outwards on his internal structures”, as he put it in a recent interview with Ballardian historian Simon Sellers. The result is roughly what Ultravox would sound like in 2011 if Foxx had never left.

Benge came to Foxx’s attention with his Twenty Systems LP, which with a ‘gear-gasmic’ attention to detail documented the development of the synthesiser in a year-by-year account of 20 individual machines introduced from 1968 to 1987. Obviously a dream appointment for the Londoner, Benge has seemingly played Rick Rubin to Foxx’s Johnny Cash – emboldening the old hawk and acting as a conduit to his former self. Comprised entirely of early analogue tech, with Metamatic’s Arp Odyssey, the CR-78 drum machine and the seminal Yahama CS8o (think Vangelis) recommissioned, Interplay even manages to invoke some of the hand-made charm, the novice imperfections and the happy randomness which riddled early synth-pop. And with Foxx joyously letting rip for a spectacular vocal performance, there is also a little of the gaiety the electro pioneers displayed as they lived out their small-town dreams. Benge is a fetishist, this much is true, but his ability to draw out such intangible essences marks him out as an artist first and foremost. The Twenty Systems project was an almighty testimony to the unfulfilled potential of the synthesiser, but more importantly where Interplay is concerned it was a treatise on how technology alters meaning.

It’s important to note that Interplay has nothing to do with regression, nor does it descend into over-familiarity. In fact, although the title is in reference to Foxx’s purportedly syncretic relationship with his attuned collaborator, it could just as easily describe both Interplay’s genuinely vital interaction with electronica’s ongoing evolution and the push-and-pull between a contemporary feel and Foxx’s classic sound.

The album begins with the sound of Foxx being sucked backwards into the mainframe, first discorporated then reformed within the corridors of perpetual circuitry. Abruptly the audio snaps into focus, assuming into a lockstep pitter. From here on in we rove a non-space virtuality, an interzone if you like. The 808 beats and EBM modulations click and clack like wire-frame fingers against the perspex backdrop, before ceding to the wet silver solder of various piercing effects, while Foxx’s vocals – taking from William Burroughs’ croak on the Naked City recordings – lag and surge on a mutilated channel. It’s in homage to the New Yorkan cold wave which the duo feasted on throughout the process; a scene which with its mythology of ‘controlling electricity’ (i.e the hands-on appeal of rudimentary synths) chimes loudly with Foxx’ increasing disdain for imitative software. Additionally Schoolwerth & Co’s devotion to harsh beauty and lo-fi violence matches Foxx’s descriptions of the original step-sequencers; that being the sound of the loudest overdriven guitar note played forever with just the application of a single finger – the same technology Foxx has been getting to grips with again on Interplay. That said, if you compare Foxx’s breadth of reference to the Wierd / Captured crew’s hermetically sealed pastiche – all circumscribed beats and slavish mimesis – you will soon get an idea as to where the new breed are going wrong.

‘Shatterproof’ is followed by the satirical, pop art ‘Catwalk’, a high-fashion surface-dream in the Bowie/Roxy/Madonna/Fischerspooner vein, with a slight tang of The Idiot-period Iggy to match the story charts Foxx’s journey through the night in a (self-effacing) quest to land a model. A highpoint of the year so far, the archetypal Foxxian sound is paired with some bulldozing sub-bass. It’s a retro-active dream come true and perfectly communicates Foxx’ exhilarated lust as he meets with the marauding flash and ugly underbelly of the fashion world – a hulking universe all of its very own, both seductive and sinister in equal measure.

On ‘Evergreen’ Foxx returns to his long-running preoccupation with an overgrown future London. There’s borrowed imagery from Ballard’s The Drowned World – tropical ruins and such like – beneath which Foxx models a sort of memoir; bearing witness to an unremitting hunger for innovation spanning a 30-year career: “I will always return to this place / for a glimpse / for a trace” he testifies “ever changing / ever new / ever restless / ever true” – the life and times of The Quiet Man, an artist perennially “overlooked and never seen / ever lost / never found” but “forever evergreen”.

Then comes ‘Watching The Building On Fire’. An expertly composed Ballardian allegory, John and his robotic gamine (Ladytron’s Mira Aroyo) scour the landscape. They see a man fall 1000 miles away, plunging from a flaming 1000-storey building located “at the edge of today”. Helplessly they relive the scene endlessly – across “a million lifetimes” – both hypnotised and tortured, always crashing in the same car. Again and again the man falls, with the duo paralysed within the looping memory. There’s a vaguely soporific air, a future daze – unshakable no matter how immediate the song in question. The vague suggestion is that actually it’s the duo that die in the fire: “sometimes you find out too late” intones Fox, while in the breakdown Aroyo whispers “Looking out from this window / over all the streets / shadows far below us / moving like a sea.”. You can assume she jumps. The track fades out into infinity with the duo trapped for eternity. Not until then do you consider the 9/11 connection. Like with the “building on fire” the images of that day – the blue sky and grey plume – will be relived in pixels long after we are dead. It’s an unforgettable collaboration – weirdo, sublime pop – and a serious thrill for acolytes of the genre.

Led by a voyaging Kraftwerkian rhythm, ‘Summerland’ is a gentle preamble to electro kiss-off ‘The Running Man’, featuring ‘real’ bass and guitar that propel the song towards a slightly hostile climax. Next up is a dose of ethereal darkwave in the shape of ‘Falling Star’. Listening to the naif preset rhythm and snow-pure synths, you can sense how far the countless years of reinvention have taken Foxx from his lowly beginnings. A contender for ‘the big single’, the cyber-gothic ‘Destination’ – with its big ululating synth riff a la ‘Plaza’ and super-massive chorus – is Foxx at his most straight-forwardly epic since The Garden.

To finish, the sombre Roedelius-esque ‘The Good Shadow’ hangs tenderly in a far-off firmament. Foxx’s voice is fading, merging with the white background. “I’ll always be with you” he reassures, retreating into the great beyond, “every day / every day”. You can bet it’ll be an emotional experience for the long-time fans. Somewhat comfortingly, somewhat tragically and in a super-chic acceptance of self, Foxx promises himself to the shadows, where he will drift the sacred geometry of the city, of all cities, for all time, as was always his ‘destination’. Time is a modern concern after all, and age is only a state of mind. A decade of copyists – from La Roux to Led Er Est wiped off the map: they should very well bow and curtsy at the feet of the man.

Nearly every year the 58-year old finds time between lectures to upload another vessel from his ever-flaring mind, so doubtlessly this won’t be the last we hear of John Foxx, but Interplay is such a perfect summation of his career that a more poetic and poignant full stop to his grand adventure would be very hard to imagine. John Calvert

Released on Richard D James’s Rephlex imprint, Zwishchenwelt (German for ‘the inbetween world’) is an international project helmed by surviving member of the legendary Drexcyia, Gerald Donald. As an undying exponent of 1st-wave Detroit techno, typically of Donald Paranormale Aktivitat is deserted, coldly mechanical and devolved sounding. He fills gaseous environs with the sound of contracting metal and retro Roland effects that spit battering acid and blue sparks onto the tense, prowling beats. It gives the impression of a hissing, grinding machine, moving scorpion-like through the snowy forests of his now native Germany. If not for the Siren-esque vocals preserving a very frail sense of the human, its sparse ambient workings would stall in the freeze, suffocating the fascinating sci-fi story at its core: a future-occult mystery where every night a blood red sun sets on the ghosts of Russian sailors, and the glare burns cataract-riddled eyes through the interstices of venetian blinds.

Based around an extremely sinister field of pseudo-scientific research known as parapsychology, the “frontier science of the mind” according to the bods, Paranormale Activitat presents a series of cinematic moodscapes channelling ideas of precognition, thought transference, mind-to-mind interrogation and various other face-whitening practices which alas are the stuff of complete fiction. Like much of Donald’s music it’s shot through with the corroded, rusting esthesis of peak-era Detroit c. 1985, which as a truly gifted audile he conjures with almost claustrophobic verisimilitude, evoking that certain ‘something in the water’ that pervaded the year. With Reagan’s all-conquering reinstatement and the “Star Wars” initiative threatening to destabilize the MAD treaty, that certain something could be summarized as fear – measuring way off the Geiger scale in the year Alan Moore began work on Watchmen. In 1981 USA defence spending was at 178 billion dollars. By 1986, it was 367 billion

By combining the two elements within such futuristic currents, the powerfully transportive Paranormale Aktivitat works like some type of alternative history of cold war espionage; a ‘second reality’ (track 11) where militarized psychokinesis is real and the almighty minds of nuero-gods clash along the Iron Curtain, their retaliations echoing back and forth like tracer fire in the lonely night air above alien Russian architecture. Methodically and meditatively elicited by a patient producer in Donald, it’s a world you could get lost in, where psychic spies hunt KGB agents for state secrets, eliminating moustached spooks through flaking plasterboard with vein-bursting, orgasmic focus. As the album continues, all kinds of shadowy figures and dangerous scenarios come to the fore amidst the throbbing, sulphuric conditions. On ‘Materialization’, in the grips of Capgras psychosis British double-agents chase mirrors and slamming doors in the deserted corridors of labyrinthine Moscowian hotels. On ‘Enigmata’ unremarkable-seeming moles relieve dim-witted sentries of their door keys, and on ‘Remote Viewer’ we watch behind a two-way mirror as bureaucratic overlords fall at the mercy of red-lipped femme fatales, who move like cigarette smoke around your body before escaping through the bowels of crumbling European cities on ‘Telemetric’. It’s a suspenseful, hypnotic invocation of your footsteps-in-the-alleyway and bugged light-fixings stuff, radiating intrigue and smoking gun dread. If you turn the lights out you can almost feel a pistol in your hand, and a silencer in the other.

“Vina” is one such super-powerful enchantress appearing on ‘Telekenisis’, whose “pleasure is high / [and] her focus key”. “She can brand you with her iron mind” Beta Evers intones, in an icy germanic accent “Good luck Vina / She makes hearts stop beating”. In sharp relief with the metallic backdrop, Ever’s luring, breathy dispassion creates a clever juxtaposition, forging a connection between the fear of Red indoctrination – symbolically a penetration of the mind – and penetration of the sexual kind.; a reoccurring motif in the tradition of late-Cold War horror.

It seems fitting that Paranormale Aktivitat was build from invisible lines of code, transmitting virtually around cosmopolitan Europe. Constructing Paranormale in increments, New York DJ/producer Susana Correia, Spanish producer Penelope Martin and vocalist Evers emailed parts to and fro with Donald until everything tessellated. They’ve composed a sleekly finessed album in physical isolation from one another, tangibly heightening the atmosphere of disassociation and paranoid silences.

Thematically, the obvious reference point is Scanners, buts it’s the sights and sounds of Ken Russell sci-fi horror Altered States most keenly felt on Paranormale Aktivitat, especially at its most cosmic on ‘Cryptic Dimension’ and ‘Apparition’. Referenced by a host of industrial and grindcore bands including Godflesh, Ministry and Agrophobic Nosebleed, the film is based on John C. Lilly’s sensory deprivation research conducted in isolation tanks under the influence of psychoactive drugs like Ketamine and LSD. Like Russell’s cult classic, Paranormal Aktivitat is hyper-vivid but flooded with the nagging suggestion that the dream, whether you like it or not, is real. Scanner’s tagline read: “Welcome To The Outer Reaches of Future Shock”, which for Gerald Donald is merely a good place to start. John Calvert

words_John Calvert

“This connection to rough or coarse behaviour also ties in to modern psychology. In psychological terms, you might think of a person’s struggle with lycanthropy as a struggle to come to terms with – or get rid of – his more primitive nature. When a man becomes a werewolf, his primal instincts, which aren’t necessarily considered to be appropriate, take over.”

Tracy V Wilson, ‘How Things Work’.

Both strange and frightening are the wolf gang.

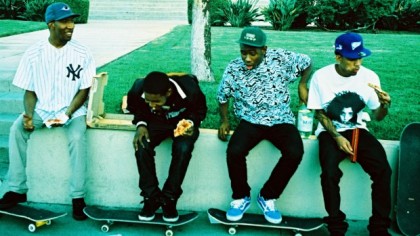

By around the age of 30 the future begins to look odd, and the next generation even more so. Sometimes it takes a baby-faced, 17 year-old borderline sociopath in a hair salon to tell you your number’s up. Or seven more just like him; a skating band of child demons from Crenshaw, Los Angeles, who right now are the most exciting hip hop act on the planet.

Taking to the LA streets on a cocktail of pills, powders, cough syrup and weed, Earl Sweatshirt and the wolf gang run riot on the video for ‘Earl’. They stack on their ollies, collapse on the pavement, scream, bare torn gums, scrap, and play games with fake blood. They simulate pulling out their hair, teeth, and on one occasion a fingernail, eventually lying on top of each other in a mass heap of overdosed corpses. Both alien and alienating, the promo coveys a world faster, harsher and more dangerously alive than the average pace and weak clarity of normal adult living. It screams ‘We’re next, here’s the door’. Every generation wants to be the last, as Chuck Palahniuk writes. To watch these post-everything, for-nothing teens go at the world, it occurs they might just see the job through.

Fucked for innocence, flush for drugs, “Black Ted Bundy[s]/Sick as John Gacey” (Vince Staples), here lies the homophobic, religion-hating, woman-hating Odd Future. Theirs is a kind of shockcore grand guignol; Droog-rap founded on stubborn, off-sync beats and deformed, bug powder production – elephantine, electric and coursing with ‘all the dread magnificence of perversity’. Imagine if Butthole Surfers hallucinated a purple Jaberwocky with the head of Eminem and the third-eye of any number of trailblazers; Flying Lotus, Madvillain, RZA, Liars, John Coltrane, DJ Screw, PiL, Boards Of Canada – all are ripe for a ‘swagging’.

Sure to inspire universal condemnation is their penchant for a truly reprehensible subject matter. On nearly every cut, and with obsessive zeal, they rap about rape; the fantasies gratuitously detailed, sickening yet sometimes nihilistically comic. It’s indefensible and chillingly inexplicable, and inevitably the hand-wringing will arrive in a torrent. The air of amorality is overwhelming, the pay off quips wince-inducing at best (“It’s not rape if you like it bitch”) but the thrills are endless – if very, very guilty. But, when it comes to living art through your favourite artists, to coin a phrase: ‘Would you rather be a snake or a poisonous snake?’ Odd Future? They’d rather be wolves. Either way, evil always wins, so ‘dominate yourself’ as Pissed Jeans would prescribe. “I’m bad milk” says founder Tyler, the Creator “…drink it”.

In the growing number of interviews with Odd Future they make sure to pour scorn on nearly everyone except their beloved Waka Flocka Flame, taking aim at the Backpackers, black pop, LA’s homegrown ‘Jerk Rap’ craze, gangsta screwfacery, hip hop bloggers and hipsters (“Ain’t no hipster mista/Fuck you in your yellow skinnies”). As Simon Reynolds has pointed out, there’s a likeness to Big Black, who also enjoyed baiting the right-on liberals with repellent content, disregarding the right-wingers as soft targets. Odd Future, however, have a quite different (arguably more deserving) quarry in the faux-hemiam millennial hipster. Their condescension of hip hop culture, evinced by the likes of Spank Rock or The Cool Kids and dating back to Weezer, deserves a response like the Odd Future phenomenon, which in its extremeness defies clever-clever parody. Despite Tyler’s best efforts, though, they will subscribe by the busload, instigating a sort of cultural gentrification. It’ll be interesting to see how far this coterie of cool-hunters and cultural nomads will go before ironic detachment begins to look like tacit approval, when Earl Sweatshirt is writing lines like this:

“Hurry up I’ve got nuts to bust and butts to nut/And sluts to fucking uppercut. It’s OF, buttercup/Go ahead, fuck with us/Without a doubt a surefire way to get your mother fucked/Ask her for a couple bucks, shove a trumpet up her butt/Play a song, invade her thong/My dick is having guts for lunch/…As well as supper, then I’ll rummage through a ruptured cunt.” [‘Earl’]

Spitting bullets from under his salon hairdryer on the accompanying video, adoring concubine fawning to his left (look again and it’s a disembodied mannequin’s head) Earl Sweatshirt is ready to think you out of existence. He is to Odd Future what Jay Adams was to the Zephyr team – the youngest, the most blazingly talented and possessed of god-given flare. He’s also by some margin the most sinister, playing off Tyler’s bludgeoning production with casual, pustular scabrousness. It’s fun to imagine quite how the fat-backed top-earners will approach guest rapping and collaboration with Odd Future, after the teens inevitably go global. In their current form it’s difficult to see where a Jay Z or Kayne West figure would fit. Even Dr Dre would seem out of his depth in the brave new world of OF. Whoever it is that steps up, the chances are their star will be subordinated to Tyler’s uncompromising vision, while the wolves close in from all around. Maybe Miley Cyrus is interested?

As well as acidly iconoclastic, the collective are hyper-creative. Of a total of 250 tracks available on Tumblr, around 150 are sensational, especially that of the sub-2 minute efforts – dislocated, coarsely effective offensives, super-charged by a ‘try anything’ love of experimentation attributable to their tender ages. They design their own art work, which ranges from the innocuous, to obscene porn shots, bloody-nosed babies and cracked-mirror images of little girls. The fissures are reminiscent of scars from extensive brain surgery, or the blurred vision which results from prolonged exposure to their tumour-activating beats.

So, how to make sense of Odd Future? Post-YouTube teen cynics with little left to discover at an early age, they bear the scars of an anomie endemic to a generation of hyper-connected childhoods. Which, from the evidence of OF’s music, makes those 90s-born kids pretty combustible. It’s almost like ‘idle hands’ syndrome, which incidentally is the very same theory served up by baffled sociologists to explain the monstrous acts described by Odd Future.

Beneath the horror stories, though, you can detect the cold facetiousness peculiar to middle-class American kids – a trait perhaps less prevalent amongst their underprivileged peers, whom prematurely burdened with adult responsibilities live the trials of hardship through ‘4real’ hip hop, rallying behind talk of overcoming adversity and ‘thug life’ authenticity. When asked by Syffal what he wants to promote, Tyler’s answer was simply “hate” (and his act). In the Southern rap tradition they’ve exchanged reality for the beyond; regional identity, oppression and the acquisition of wealth for Ritilan and Jeffrey Dahmer. There’s little talk of smooth sexual prowess and Lamborghinis. There’s no objective to speak of at all, in fact, or anything approaching legitimate disaffection. Only a cruel contempt for generally every human being they’ve encountered in life or online – part and parcel, you feel, of the inured, hard-edged disposition native to big city adolescence.

It might be argued they’re just a bunch of teenagers playing at a effectively meaningless type of hooligan art. But that would be remiss of how anciently primal Odd Future sound. The more you listen, the more Tyler grows in stature, and the longer his shadow, the evanescent wickedness of young masculinity arousing before finally raging. It’s the type of senseless black culture bomb that would have Alex Haley turning in the grave Odd Future are about to dig up. Whether the product of advanced desensitisation or the modern disease’s final disaster (“Plenty of us are bastards. Most of us.” Hodgy Beats told the New York Times), what argument can there really be against the zeitgeist? Either way they’ve touched a nerve this last year – a naked lunch served cold to the establishment and the hop-hop royalty in equal helpings.

Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All are Tyler, the Creator (aka Ace, evil alter ego Wolf Haley, The Creator), screwed down dranker Mike G, the blunted-out Domo Genesis, star-in-the-making Earl Sweatshirt, Hodgy Beats and Left Brain (whom together are Mellowhype), singer Frank Ocean, The Super 3 aka The Jet Age of Tomorrow and producer Syd. Each party have released solo albums, available free on Tumblr (eleven between them in the last year including the covers heavy Radical and the original self-titled mix-tape). An even greater mystery than the whereabouts of Earl Sweatshirt (missing, presumed grounded) is the last name on the list – a silhouetted figure rumoured to take the form of a female. All but uncredited on the site but glimpsed on the periphery of their videos, she plays an unspecified but reportedly despotic role in production. In a recent interview Mike G described ‘Syd the Kid’ as “the brains of this shit.”

Currently trending on Twitter and set to debride contemporary hip hop in the next year and all years, here’s eleven of Odd Future’s best. Enjoy your immolation, let it hurt… the future often does.

1. Tyler, The Creator (featuring Hodgy Beats) – ‘French’

Less of a promo and more of an uprising, the spectre of Larry Clarke looms large on ‘French’, as the kids, basking in moral misery, partake in a kaleidoscope of abject skulduggery. At only one minute and 44 seconds long ‘French’ remains one of the great lifestyle introductions in video history, rubbing shoulders with the likes of ‘Nothin’ But A G Thang’ and ‘Lap Dancer’. When Tyler explodes onto screen you get the creeping sensation you’re watching history in the making. One of the best ‘What the fuck was that?!’ moments in recent memory.

The “Oh No, Mister Stokes” line is in reference to Chris Stokes, the music producer alleged to have molested Raz B and other members of R&B boyband B2K (of ‘Bump Bump Bump’ fame) when under his stewardship. Mocking your revulsion, Tyler simply turns his eyeballs backwards into a rather disturbed noggin.

2. Earl Sweatshirt – ‘Earl’

Produced by Tyler and Left Brain, the second track from the prodigy’s 2010 album requires a strong stomach, even for the most hardened of death metal lyricists. For all his puerility, though, the school-age rapper weaves phonetic pyrotechnics into his producers’ bellowing, toneless overdrives. A speaker-busting tour-de-force.

3. Mellowhype – ‘Gram’

From their impossibly strong BlackenedWhite collaboration, on ‘Gram’ Hodgy Beats and Left Brain feed their brand of stoner-funk macabre through a fitting Wurlitzer with the batteries dying. The discombobulated cycle of snares, kicks, and a pitched-down dog sample represents the avant garde side of Odd Future; more Flylo than Eminem.

4. Tyler, The Creator – ‘Splatter’

Reams of nightmarish imagery, Tyler at his most venomous and fat beams of Cronenburg-ian horror synths churning in the background like Wendy Carlos unconscious on her Moog – it doesn’t get any more squeamish than ‘Splatter’. “Someone tell Satan I want my swag back” Tyler growls before bringing matters to a merciful close with a leering ‘Abracadabraaaaaaaaaa”. If you can’t be good, as the old adage goes, at least be good at it. Thrilling stuff.

5. Domo Genesis – ‘Kickin’ It’

More studio trickery from Left Brain (with Tyler in tow). Domo Genesis’ heavy-eyelids flow dovetails perfectly with the production on ‘Kick It’ (christened ‘dystopian weed rap’ by The Fader), reminiscent of Outkast’s ‘She Lives In My Lap’ and co-produced by the besuited dwarf from Twin Peaks. Genesis has been been likened to both Curren$y and up-and-comer Wiz Khalifa, whose forthcoming album is also titled Rolling Papers, sparking accusations of plagiarism from Tyler on Twitter. The situation was quickly resolved, however, after Khalifa sampled Alice Deejay’s ‘Better Off Alone’ for chart-bound ‘Say Yeah’, prompting widespread laughter and some pointing.

6. Tyler, The Creator – ‘Oblivion’

From the Radical album, here the self confessed “depressed emo faggot” chokes up something altogether unique. A throwaway, two-and-a-half-minute descent into loathing and overt self-loathing, ‘Oblivion’ is driven by an relentless beat, turning the screws rightly. Part sadomasochistic atonement, part primal reverie – after the bizarre and distressing opening skit, Tyler proceeds to reverb his voice into nothingness (or ‘oblivion’), yet continues with a desultory stream-of-consciousness rap.

Most unnerving is his voice, which appears somehow different – gruffer and more intense. In other words, he sounds possessed. Stranger still, all his talk of conquering white meat, taking white drugs, murdering his manager with an iron, and his unexplained declaration “I’m just a white boy with no remorse” concludes with “I just need someone to talk to”. Extremely creepy. And they say Kayne West is conflicted. With Hodgy Beats in tow, the teetotal, fiercely atheist 19-year-old made his national television debut on Late Night With Jimmy Fallon this February the 16th past, performing his new single ‘Sandwitches’. As was predicted the notorious green balaclava received an airing.

7. Earl Sweatshirt (featuring Vince Staples) – ‘Epar’

Runner-up for best cut on Earl, ‘Epar’ contains the very best line from any Odd Future track hitherto – the much-quoted “You’re Fantasia and the body bag’s a fucking book”. By way of explanation, the lyric comes after Earl spots the remains of Vince Staples’ latest kill, stashed where he hides the “marijuana in the condom”. Staples warns him “Don’t touch it, or even look/You’re Fantasia and the body bag’s a fucking book”; the former X-factor winner is reportedly illiterate. M.I.A since July and due to miss Coachella in April, it remains unsure if and when Sweatshirt will turn up, but a ‘Free Earl’ t-shirt will shortly be available on the Odd Future site. And in case you didn’t twig, ‘Epar’ is rape spelt backwards.

8. Tyler The Creator – ‘Yonkers’

More abandonment angst, more schizophrenia, more vomiting. Released by XL Records who signed the teen on Valentine’s day, ‘Yonkers’ is the first single from Tyler’s imminent LP Goblin. Amassing 100,000 views per day since its unveiling, the accompanying video is written and directed by the teenager, a young man not yet old enough to know the meaning of compromise. With the cockroach and the telepathic (or ‘intra-diegetic’) rapping there’s a tang of William S Burroughs about it, while the spry arrangement fits perfectly with the verité touches and clean monochrome. Winner of best line goes to “Swallow the cinnamon” or the ‘sin-of-men’.

9. Mellowhype – ‘Dead Deputy’

Another inspired cut from BlackenedWhite, the exhilirating crunk lite of ‘Dead Deputy’ showcases Hodgy’s rapping and Left Brain’s signature production style. Incorporating singing and melody, the LP is comparatively leavening, but grimy enough to accommodate the dark influence of Tyler on two tracks. Left Brain energises the verbose rhymes and crunk-holler “Kill ‘Em All, Kill Em All” with a technical sophistication lightyears beyond his age.

10. The Jet Age Of Tomorrow – Journey To The 5th Echelon

Jet Age’s spangled, retro-futurist 5th Echelon has more in common with Odd Nosdam than Insane Clown Posse. Tonally in diametric opposition to the future as predicted by their associates, but no less odd, this subtlety beautiful album of acid-fried circuits and listless grooves reveals Tyler to be a shrewd scout and Odd Future as an act with both eclectic dimension and a seemingly endless supply of talent. There’s some rape and murder on there too, but let’s give them the benefit of the doubt. From a 19-song giant, the highlights include ‘Want You Still’ featuring a star turn from skeezy sweetie-pie Kilo Kish, and warping candy cloud ‘Her Secrets’.

11. Tyler, The Creator – ‘Sandwitches’ (live solo performance)

The Odd Future anthem, performed last Christmas in The Roxy, LA. Setting the tone for the punkish pow-wow that ensues, it begins with the Marshall Mathers-esque line “Who invited Mr ‘I Don’t Give A Fuck’/Who cries about his daddy on a blog/Cause his music sucks’. It’s another disquietingly candid slice of self-laceration from Tyler, whose father left home when he was a baby. Factor in the menacing build-up (worsened by the stage lighting, illuminating the black hole where Tyler’s face should be), that abominable two-note motif, and the crowd’s chant of “Wolf Gang…Wolf Gang”, the cumulative effect is something akin to The 1933 Nuremberg Rally, with Christmas decorations. There he was, Mr Hitler, ablaze with consolidated power and on the crest of total domination. The similarities are uncanny.

Tyler, the Creator’s next album Goblin will be released on XL Records.

This record gives you migraine. Ha, funny one. Like in the song. But it’s true – a tangible stiffening above the neck and a centimetre behind the eyes. The impulse is to crack your jaw the way people crack their knuckles. A sciatic irritant of an album – exasperating, declamatory and asininely triumphant from start to finish – Content tests your concentration and the enamel on your teeth. Stand up, sit down, hyperventilate, bite your nails, grow a moustache, burn your clothes, rent a mini-digger, take a photo of a man walking, buy a monocle, laugh outrageously until you scare yourself, learn to fence, learn origami, burn your clothes, go to church, alphabetize you cereal boxes or wear a gas mask when driving, but do anything to escape its clammy grasp and the torturous void that is total neural non-engagement. It’s shoe shopping with your mum when you’re nine, it’s watching Blockbusters with Bob in 1986, it’s Human Traffic; the extended version, it’s waiting for Neil from work to get to the point of his story, it’s a Ron Howard film, it’s Broken Social Scene Play The Hits, it’s Mad About You starring Paul Reiser and Helen Hunt, it’s a sigh, in a Rumbelows, in Wrexham, 27 years ago, on a wet Tuesday. Your only lucid thought when listening to Content is something like “hmmph, this is disappointing, like the way life is, and always will be, forever”.

A repulsive bit of snark there, I hear you say… and if only the once great Leeds band deserved a more measured response. But after a week of desperately trying to like Content – entertainment on a par with an emergency tracheotomy – my critical faculties are shot, reduced to random sex sounds, Cockney rhyming slang and swinging punches in a cupboard.

After grimacing like emphysemic Russians for a couple of years they’ve managed a pellet of something approaching the sound of ‘quintessential’ Gang Of Four. Once a radical new mode of dissent – a weeping laugh, dancing the h-bomb – so numerously has it been stripped for parts that any semblance of treasonous cool and incisory newness has long since perished, bleached in the fires of 2004, besmirched by the shit-flecked tendrils of lesser spirits. You’d have thought they’d have picked up on this fact. It’s possible they did, but calculated that collecting their long deserved reparations was going to take playing it safe.

Only it’s not just safe; this is a defanging. Out goes the scything atonality, the brooding stretches of space, the shadows and the tensile pulse of Thatcher-era upheaval – basically anything that made them great before Here. What you’re left with is a dead zone between funkless funk and berkish indie-rock, both rendered blithely anodyne and abrasively insipid, so very little of which sticks in the memory. 30 years past their prime they’ve returned with the same old rope, but purged of its incendiary social context, the shock of the new, and the burning intent of a group of young leftist heroes. And what do you get if you take the fish from the water? A dead trout and a very bad smell. On Content, the aesthetic has never sounded more weak and weary than in the hands of the very men who invented it.

For a record made from 99% perspiration and another 99% careful contrivance, its almost destitute of artistic prudence. The songs are flat and gross, further exacerbated by Gill’s frowsy, dim production, comparable to a senile man driving a car – heavy on the pedal, heavy of the brakes and no real destination in mind. Any remaining hope of a defining agent finding purchase in this soup is extinguished by rampant over-egging on the part of each individual member, who in the end cancel each other out with inelegant force.